No último diário, eu falei sobre os princípios gerais do combate. Nesse texto, entrarei em maior detalhe em algumas de suas regras específicas: os efeitos de terreno, mobilização e situações especiais de combate.

Os efeitos de terreno

Como eu expliquei no último diário, o combate em Os Triunfos de Tarlac é definido por rolagens de dado. Cada jogador em batalha rola uma quantidade de dados correspondente ao número de fichas de batalhão do combatente com menos batalhões. Cada rolagem perdida custa ao jogador uma ficha, progressivamente diminuindo seu exército.

Tamanho e sorte, obviamente, eram apenas dois ingredientes do caos que era a guerra medieval. Tão ou mais importante era onde o combate acontecia.

Em Os Triunfos de Tarlac, rolagens são modificadas pelos tipos de terreno das casas em que a batalha acontece. Estes modificadores agem como penalidades que subtraem um ponto de cada dado rolado:

| Tipo de terreno | Atacante | Defensor |

| Floresta | – 1 para cada dado rolado | – |

| Pântano | – | – 1 para cada dado rolado |

| Travessia de Rio | – 1 para cada dado rolado | – |

| Crannóg | – 1 para cada dado rolado | – |

| Castelo | Não pode ser atacado | – |

Alguns tipos de terreno afetam negativamente atacantes; outras, defensores, por razões que expliquei em detalhe no último diário.

Uma única casa pode ter mais de um tipo de terreno – ex. um local pode conter tanto uma travessia de rio quanto uma floresta. Neste caso, todas as penalidades aplicáveis são levadas em conta no resultado.

Castelos e cercos

Casas que contenham um castelo possuem uma penalidade singular: elas não podem ser ocupadas por peças inimigas, tampouco atacadas. O único jeito de anular este efeito é montando um cerco.

Em termos de jogo, isto consiste em terminar a rodada com pelo menos três exércitos de uma mesma coalizão em casas adjacentes ao castelo.

Isto é bastante difícil em termos de gameplay, pois exige que um jogador a) tenha três aliados no tabuleiro e b) neutralize a maioria dos inimigos antes de iniciar o cerco. Se houver exércitos inimigos demais em jogo, eles interceptarão as forças sitiantes, transformando a manobra em uma batalha normal. Se todos os inimigos forem derrotados antes do cerco, a fase de expedição termina antes que o cerco possa acontecer.

Ruínas do castelo de Quin, Co. Clare. A espessura das paredes dão uma boa ideia de quão difícil esses castelos eram de se tomar.

Castelos são poderosos, mas raros. Apenas os ingleses têm acesso a eles, e há apenas dois castelos no tabuleiro: Quin e Bunratty.

Assentamentos irlandeses não têm as mesmas proteções e podem ser atacados diretamente. A exceção são os crannógs.

Esse era o nome de ilhas lacustres artificiais (ou artificialmente reforçadas) onde reis irlandeses às vezes construíam fortalezas. O lago que as rodeava providenciava defesa contra atacantes, aplicando a mesma penalidade de uma travessia de rio.

Lago Inchiquin, localização de um crannóg na época de Os Triunfos de Tarlac.

De um ponto de vista tático, tanto as penalidades de terreno quanto esses regras especiais de assentamentos pareciam funcionar bem nas nossas jogatinas.

O problema era o que acontecia imediatamente depois.

Everybody, rush B

Um ou dois dias de testes depois, percebemos que todas as nossas campanhas terminavam com uma reconstituição da Batalha dos Cinco Exércitos.

Os jogadores que controlavam facções irlandesas, embora individualmente mais fracos que os ingleses e dispersos pelo mapa, tinham plena capacidade de segurar o inimigo até que seus aliados chegassem.

Como resultado, a invasão inglesa de Thomond de 1276 – que, historicamente, foi tão bem sucedida que mal encontrou resistência – se tornou um desafio impossível. Jogo após jogo, a facção inglesa nunca conseguia sequer tomar Clonroad, quanto mais manter o rei local sob seu controle.

Não havia dúvidas: apostar tudo em uma batalha campal era a estratégia ótima para vencer o jogo.

O problema é que isto não fazia sentido historicamente.

Por que os ingleses de Tarlac estavam apanhando tanto se os da vida real obtiveram tanto sucesso (pelo menos, em um primeiro momento)?

Olhando por outro lado, se decisões como as que estávamos tomando eram de fato viáveis, por que os irlandeses do século XIII perdiam tanto tempo com escaramuças e estratégias fabianas?

Para entender o que havia dado errado, precisei vestir meu uniforme de historiador, separar meu dicionário de irlandês e voltar para as fontes.

Eu repassei o material que havia levantado para minha tese e reli atentamente todas as descrições de fugas, manobras militares e marchas para lugares inóspitos.

O que eu descobri nessa segunda leitura, que havia ignorado da primeria vez, é que os comandantes irlandeses nãoc orriam de um lado para o outro para lutar, e sim para recrutar seus exércitos.

A maioria das campanhas eram ataques surpresa, de que os reis em questão só se davam conta quando descobriam de que seus aliados já haviam capitulado. Ou pior: quando enxergavam o exército inimigo montado cerco do lado de fora das muralhas.

Se eles dessem sorte e não fossem imediatamente rendidos, tudo o que lhes restava era correr o reino com sua guarda pessoal, torcendo para chegar em seus aliados e mobilizá-los antes que seus inimigos os alcançassem.

No fundo, o problema do meu sistema é que ele ignorava completamente a velocidade de comunicação. Como líderes de Crusader Kings, que podem mobilizar suas populações inteiras com um clique de seus mouses, eu assumia que reis medievais eram informados imediatamente do que acontecia e tinham um exército esperando sentado em seu pátio, aguardando apenas a ordem para começarem a marchar.

![Image - 529299] | Monty Python | Know Your Meme](https://i.kym-cdn.com/photos/images/original/000/529/299/9fe.jpg)

Condições de mobilização

Minha primeira mudança foi implementar condições específicas de mobilização. Em vez de fazer jogadores comprarem fichas de batalhão ao mesmo tempo, no início da fase de expedição, eles só poderiam fazê-lo se uma das condições abaixo fosse cumprida:

1) Se eles forem os primeiros a jogar no cenário

2) Se eles fossem atacados

3) Se uma outra facção mobilizada viajasse até sua capital e os mobilizasse.

4) Se notícias da guerra chegassem até ele.

Para facilitar a conta, eu decidi que a “velocidade” das notícias seria igual às dos exércitos: seis casas por turno – ou cerca de 25km-35km/dia, na escala do nosso mapa. Como isto correspondia à maior parte do tabuleiro na maioria das vezes, resolvi simplificar ainda mais e tomar “uma rodada” como o atraso médio das notícias.

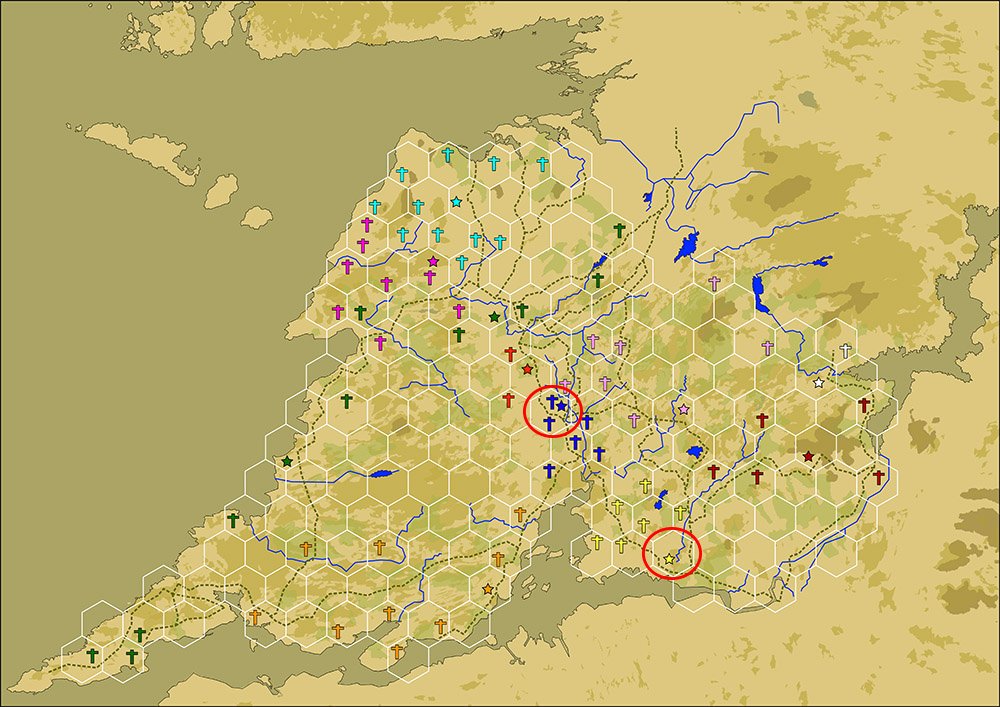

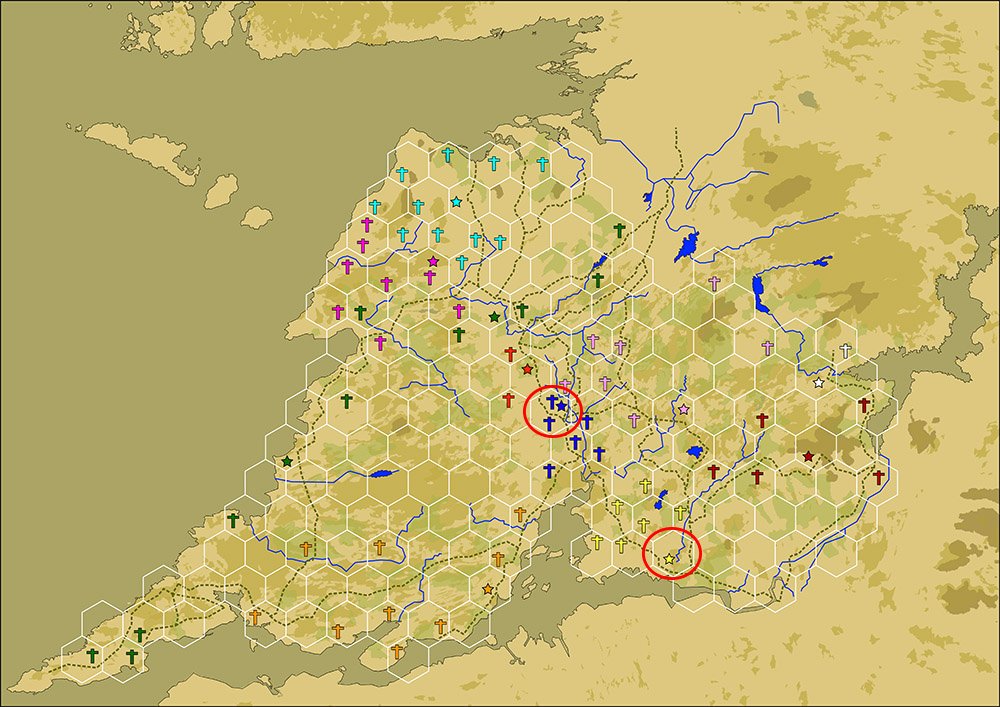

Mas fazer esse sistema funcionar como jogo ainda apresentava um desafio, que nosso mapa deixa claro:

Clonroad, a capital gaélica de Thomond (em azul), fica figurativamente do lado de Bunratty, a capital inglesa. Isto significa que um jogador que controle a facção inglesa pode atacar seu ocupante no primeiro turno enquanto ainda estivesse desmobilizado, encerrando a guerra antes mesmo dela começar.

Obviamente, esse não era um problema do jogo mais do que um problema dos próprios O’Briens. Os ingleses não escolheram a localização de seu castelo à toa. Segurar a rédea do rei de Thomond era sua razão de existir.

Mas nem só de rapidez se constrói uma vitória. Ao contrário do que sugerem games como Total War, exércitos não marchavam o tempo todo em formação, descansados e prontos para lutar. Eles andavam em colunas – às vezes, com quilômetros de comprimento – que precisavam ser reorganizadas antes do contato acontecer. Tempo suficiente para que um exército defensor montasse uma fuga se visse que a situação não lhe era favorável.

Sim, esse defensor ainda enfrentaria tropas de vanguarda, mas seriam uma fração do contingente total de seus oponentes. Para reis atacados em suas capitais, a chance de fugir era ainda maior, pois contavam com fortificações, obstáculos e defensores dispostos a ficarem para trás segurando o inimigo.

Rolagens de desengajamento

Resolvemos implementar essas ações com uma mecânica chamada desengajamento.

Sempre que um exército ataca outro – ou ataca a capital de um jogador desmobilizado – o defensor tem direito de tentar de desengajar. Para isto, ele e o jogador atacante realizam uma rolagem de combate normal, com todas as penalidades de terreno, mas rolando apenas um dado.

Este dado representa as tropas de vanguarda e retaguarda que trocam escaramuças enquanto as forças principais se mobilizam – para fugir ou para lutar.

Se o atacante vencer a rolagem, os exércitos continuam engajados – ou, no caso da capital de um jogador não-mobilizado, o defensor automaticamente é derrotado. Já se os dados favorecerem quem está defendendo, este jogador escapa do ataque e se ganha o direito de se mover uma casa para qualquer direção.

Ao contrário de rolagens de combate normais, rolagens de desengajamento não provocam baixas de nenhum dos participantes.

Resultado

Ao implementar essas mudanças no jogo, o gameplay mudou literalmente de uma partida para outra.

Jogadores que antes percorriam sempre as mesmas rotas se viram obrigado a explorar cantos distantes do mapa. Aqueles que controlavam facções distantes do centro do tabuleiro subitamente se tornaram importantes.

Antes, a distância era apenas um empecilho até chegarem na inevitável batalha coletiva envolvendo todos os jogadores. Agora, aliados posicionados nas fronteiras do reino funcionavam como portos-seguros para aliados combalidos.

Se há um porém que posso fazer é que as regras funcionaram até bem demais. A mecânica de desengajamento permitiu que mesmo exércitos combalidos prolongassem a fase de expedição por vários turnos, obrigando inimigos a persegui-los até os cantos mais inacessíveis do mapa.

Em nosso último teste, um de nossos membros resolveu perseguir essa estratégia ao extremo, insistindo em “lutar” com apenas uma ficha de exército depois de todos os seus aliados terem sido derrotados.

Infelizmente para os outros jogadores, ele teve uma incrível sorte no dado, o que fez com que prolongasse a fase de guerra por mais de vinte minutos.

Por um lado, isto é exatamente o que os comandantes irlandeses faziam nas guerras da época. Por outro, a experiência se mostrou enfadonha para todos os jogadores que já tinham se desmobilizado naquele turno – e que não tinham o que fazer senão esperar sua derrota inevitável.

Esse é um problema que ainda estamos tentando resolver – se não mudando as regras, ao mesmo criando recompensas “meta” para encorajar jogadores a agir diferente. Por exemplo, penalizando aqueles que prolongarem a guerra por mais de X turnos, ou tornar uma derrota em combate mais custosa que uma fuga ou rendição.

Para isso, contudo, serão precisos mais testes.

Conclusão: um jogo à serviço da pesquisa

Esse “bate-e-volta” para criar as regras avançadas de combate me deixou bastante feliz, pois me mostrou que nosso jogo está cumprindo a missão a que veio: me ajudar a refinar minha pesquisa de doutorado.

Graças aos problemas que meus jogadores encontraram no tabuleiro, fui forçado a repassar minhas evidências e encontrar um novo modelo de explicação para os acontecimentos que estou estudando.

É uma vitória tão grande que compensou todos os perrengues. Até mesmo passar horas a fio perseguindo meu colega que insistia em desengajar…

In the last dev diary, I talked about the general principles of combat. In this post, I will get into more details about some of its more specific rules: terrain effects, mobilization and special combat situations.

Terrain effects

As I explained in the last diary, combat in The Triumphs of Turlough is determined by dice rolls. Each player in a battle rolls a number of dice equal to the number of battalion tokens owned by the player with the fewer battalions. Each lost roll costs a token, gradually reducing a player’s army.

Obviously, strength and chance were but two ingredients of the chaos of medieval warfare. Just as – if not more – important was where combat took place.

In The Triumphs of Turlough, combat rolls are modified by the types of terrain of the hexes in which the battle occurs. These changes act like penalties that subtract a point from each rolled die:

| Terrain type | Attacker | Defender |

| Wood | – 1 for each die rolled | – |

| Bog | – | – 1 for each die rolled |

| River crossing | – 1 for each die rolled | – |

| Crannóg | – 1 for each die rolled | – |

| Castle | Cannot be attacked | – |

Some terrain types negatively affect attackers; others defenders, for reasons I explained in detail in the last diary.

A single hex can have more than one terrain type – e.g. it can be both a river crossing and a wood. In this case, every applicable penalty is taken in account when calculating the results.

Castles and sieges

Hexes housing a castle have a unique penalty: they cannot be occupied by enemy pieces or attacked. The only way to nullify this effect is by besieging them.

In gameplay terms, this consists in ending the round with at least three armies belonging to the same coalition positioned in surrounding hexes.

This is quite difficult to accomplish, as it requires that a player a) have three allies in the game and b) neutralize most (but not all) enemies prior to beginning the siege. If there are too many enemies in the board, they will intercept the besieging forces, turning the siege into a regular battle. If all enemies are defeated, the campaign ends before the siege can happen.

Ruins of Quin Castle, Co. Clare. The thickness of the walls shows why these castles were so difficult to take.

Castles are powerful, but rare. Only the English have access to them, and there are just two of them in the map: Quin and Bunratty.

Irish settlements do not have the same defenses and can be directly attacked. The exception are the crannógs.

This was the name of artificial (or artificially reinforced) lacustrine islands in which Irish kings sometimes built strongholds. The lake around them provided shelter against assailants, applying the same penalty as a river crossing.

Lough Inchiquin, site of a crannóg in the time of The Triumphs of Turlough

From a tactical standpoint, both terrain penalties and the special rules for castles and crannógs seemed to work fine in our matches.

The problem was what happened soon afterward.

Everybody, rush B

One or two days of testing later, we found out that every single one of our campaigns ended with a re-enactment of the Battle of the Five Armies.

Players that controlled Irish factions, although individually weaker than the English and dispersed around the map, were fully capable of holding the enemy down until their allies arrived.

As a result, the 1276 English invasion of Thomond – which, historically, was so successful it barely faced resistance – became an unwinnable challenge. Match after match, the English faction never manage to take Clonroad, let alone control the regional king.

There was no question about it: betting everything in a pitched battle was the optimal strategy to win the game.

The problem is this made no sense, historically speaking.

Why were the English in Turlough taking so bad a beating if in real life they were so successful (at least at first)?

Or, to put things differently, if decisions like the ones we were making were indeed viable, why did the 13th century Irish waste so much time with skirmishes and Fabian strategies?

To understand what had gone wrong, I had to put my historian’s uniform on, open the dictionary of Irish language and look back at the sources.

I went over the material I had collected for my thesis and attentively reread every description of flights, military maneuvers and marches to isolated places.

What I found out in this second reading that I had missed the first time around is that Irish commanders didn’t run back and forth to fight, but to recruit.

Most campaigns were surprise attacks, which the kings in question only noticed when they received word that their allies had capitulated. Or even worse: when they spotted the enemy on the other side of their walls.

In the off-chance that they weren’t immediately forced to surrender, everything they could do was keep running around the kingdom with their personal guard, hoping to reach their allies and mobilize them before their enemies caught up with them.

In the end, the problem of my system is that it completely ignored the speed of communication. Like rulers in Crusader Kings, that could raise their whole kingdom’s levies with the click of a mouse, I assumed medieval kings were immediately informed of what happened and had an army just sitting on their porch, waiting to get in action.

![Image - 529299] | Monty Python | Know Your Meme](https://i.kym-cdn.com/photos/images/original/000/529/299/9fe.jpg)

Conditions for mobilization

My first fix was to implement specific conditions for mobilization. Instead of making players buy battalion tokens at the same time, in the beginning of the expedition phase, they could only do so if one of the conditions below were met:

1) If they were the first to play in the scenario

2) If they were attacked

3) If another mobilized player travelled to their capital and mobilized them

4) If news from the war reached them.

To simplify things, I established that news “travelled” at the same speed of armies: six hexes per turn – or around 25km-35km/day according to our map. Since this corresponded to most of the board in the majority of situations, I decided to simplify it ever more and take a single round as the average speed of communications.

But making this system work as a game presented another challenge. One that our map made obvious:

Clonroad, the Irish capital of Thomond (in blue), was figuratively next to Bunratty, the English capital. This meant that a player that controlled the English faction would attack its occupant in the first turn while the Irish were still demobilized, ending the war before it had even started.

Naturally, this wasn’t a problem of our game more than a problem for the O’Brien themselves. The English didn’t choose to build a castle there on a whim. Holding the leash of the king of Thomond was its reason for being.

But swiftness alone was not all it took to secure a victory. Contrary to what the Total War and related games suggest, armies didn’t march all the time in formation, rested and ready to strike. They moved in columns – sometimes, kilometers long – that needed to be reorganized before contact occurred. Enough time for a defending army to stage a retreat if it saw that the situation wouldn’t turn out in their favor.

Yes, this defender would still face vanguard forces, but they’d be a fraction of the total contingent of their opponents. For kings attacked in their capitals, the chance of escaping was even higher, for they counted with fortifications, obstacles and defenders willing to stay behind and delay the enemy.

Disengagement rolls

We decide to implement these actions with a mechanic called disengagement.

Every time one army attacked another army – or the capital of a demobilized player – the defender has a chance of disengaging. To do so, both they and the attacking player take a normal combat roll, with all applying terrain penalties, but rolling a single die.

This die represents the vanguard and rear-guard troops that traded blows while the may forces mobilize – either to retreat or to fight.

If the attacker wins the roll, the armies remain engaged – or, in the case of an attacked settlement, the defender automatically surrenders. If the dice favour whoever is defending, on the other hand, that player escapes the attack and earns the right to move a single hex in any direction.

Players attacked in this fashion while still demobilized get the right to mobilize, but they do so with a single battalion token. This represents household troops that were always present at the leader’s side.

Unlike normal combat rolls, disengagement rolls do not inflict casualties on either party.

Result

After implementing these changes, the gameplay changed literally from one match to the next.

Players that always took the same routes were forced to explore the edges of the map. Those controlling factions situated far away from the center of the board suddenly became important.

Before, distance was merely a hindrance before the inevitable battle royale involving every player. Now, allies residing at the borders of the kingdoms acted as safe havens to their beaten friends.

If there is any fault I can find with the new rules is that they worked too well. The disengagement mechanic allowed even armies on their last legs to prolong the expedition phase for several turns, forcing enemies to pursue them until the very last hexes of the map.

In our latest test, one of our team members decided to follow this strategy to the extreme, insisting on “fighting” with a single battalion token after all of his allies had been defeated.

Unfortunately for the rest of the players, he was incredibly lucky at the dice, which extended the expedition phase for over 20 minutes.

On the one hand, this is exactly how Irish commanders acted during the wars of the period. On the other hand, the experience proved to be wearisome to players who had already demobilized in that round – and had nothing else to do but to wait out his inevitable defeat.

This is a problem we are still trying to solve – if not by tweaking the rules, at least creating “meta” rewards to encourage players to act differently. For example, by penalizing those who prolong the war beyond X turns, or by making a defeat in combat more onerous than a retreat or surrender.

This, however, will require further tests.

Conclusion: a game in service of research

This “back-and-forth” to create advanced combat rules made me really happy, for it showed me that our game is fulfilling the role it was created to do: helping me refine my PhD research.

Thanks to the problems my players faced in the game board, I was prompted to review my evidence and find a new explanatory model to the events I was studying.

This is big enough a win that it made up for every annoyance along the way. Even wasting turns on end chasing my colleague that insisted in disengaging…

0 comentários